|

How UGRs impact safety

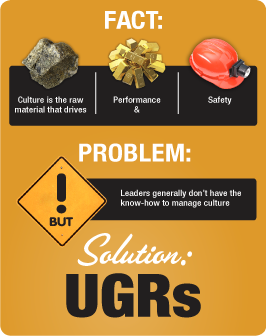

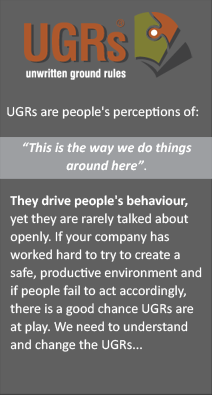

The Power of Workplace Culture In their landmark book “corporate culture and performance”, authors Kotter and Heskett found evidence of an irrefutable truth – that workplace culture drives performance. In what had previously been based on intuitive logic, the research underpinning this book provided evidence that corporate cultures impact on an organisation’s long-term economic performance. Organisations with strong workplace cultures increased revenues by almost five times more than that of organisations with poor cultures. The book was not only a landmark because of the empirical evidence it provided. The text proved to be a significant catalyst in terms of getting leaders, perhaps for the first time, to seriously consider their own organisation’s culture. It’s clear. Culture drives performance. And UGRs holds the key to culture transformation. But what about safety?

Does culture also drive safety in mining? The US National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (NIOSH) thinks so. They say: “The way to improve the safety of miners is through creating a positive safety culture”. A continent away, in one of the major mining nations in the world, South African Prof Philip Frankel recently published his book ‘Falling Ground; human approaches to mines safety in South Africa’ - one of the first non-academic works to systematically examine mine safety. In this ground-breaking work he draws on a database of mining safety case studies across 35 South African mines in all sectors – contrasted with the experience of other major mining nations, including Australia, Canada, USA, China, India, Peru, Chile and Argentina - to structure a map for reconfiguring and improving safety in mining. One of his central findings? That mining safety needs a “culture change”. Perhaps the strongest evidence comes from the 126-page report on the worst mining accident on American soil in almost a half-century: the devastating April 5, 2010 explosion at the Upper Big Branch coal mine in West Virginia which killed 29 of a team 31 miners. Led by former US Mine Safety and Health Administration (MSHA) head Davitt McAteer, the report provides ample evidence for the criminal prosecution of top Massey officials, for, amongst other charges, “leading a corporate culture” that allowed the disaster. “Regulation alone cannot ensure a safe workplace for miners,” McAteer writes in the foreword to his report. “It is incumbent upon management to lead the way toward a better, safer industry... through the creation of a culture in which safety of workers truly is paramount.” A significant part of the report is dedicated to investigating ‘The Culture of the Operator’. It finds that owner Massey Energy’s top leadership first caused, and then allowed the perpetuation of a workplace culture that ultimately lead to the creation of a climate that would capacitate this devastating, yet avoidable disaster. In the report, McAteer draws a few parallels between Massey Energy, then a top-5 US coal producer, and Peabody Energy, the USA’s largest coal producer. He quotes Don Blankenship, then Massey Energy CEO, protesting that Massey worked in “difficult underground conditions” and maintaining that their safety record was “about average.” Blankenship: “... we’re a big producer, so fatality numbers tend to get big, even with your best efforts.” But McAteer’s report found that this assertion just wasn’t true. Massey barely averaged 18 million tons per fatality. By contrast, Peabody averaged a staggering 296 million tons of coal for every miner lost. And to drive the point home: the year of the Massey explosion, 2010, was the safest year in Peabody’s 127-year history: in this year their US operations outperformed the industry average by 49 percent, and their Farmersburg Mine in Indiana was recognized as the safest large US surface coal mine. Proof enough that safety need not come at the expense of production. The difference between the two cultures? McAteer finds that at Massey “There existed a culture where it was acceptable to mine unsafely”, while every indication suggests that there exists a culture which supports personal accountability at Peabody. A culture where every employee commits to the safety vision, and employees at all levels are held responsible for safe behavior and practices at work and away. A culture where peers hold one-another accountable for safe behaviour; where people care about each other, and where leaders actually do what they say they are going to do. Yes, indeed, workplace culture does drive safety in mining as much as it drives production performance. But how is culture formed? The Upper Big Branch accident report may also hold the answer to this critically important question. We have already mentioned the Massey- Peabody production vs. safety comparison, which demonstrates a staggering 94% variance in their fatalities per million tons produced safety ratio. Even though their safety stats lay at different ends of the scale, Massey and Peabody also had much in common: namely the fact that their leaders caused, or allowed, their prevailing culture to exist. Whilst the leaders at Massey undoubtedly never intentionally set out to create a culture “where it was acceptable to mine unsafely”, the accident report found that their way of doing things nonetheless caused, and then allowed, their prevailing culture. We contend that the same must be true for Peabody: their way of doing things has also been caused, and allowed, by their leaders – except that in their case it was willful. There can be little doubt that the creation of workplace culture is a matter of strategic intent – either by design, or by omission. We can’t teach you the Peabody way. But through UGRs we can help you to create your own winning culture: where people are safe, whilst being personally accountable for reaching production targets.

|